The yoga “scene” in the west is driven by systems. We have Iyengar Yoga, Ashtanga Yoga, Vinyasa Yoga, Yin Yoga, Restorative Yoga and on and on. New ones are being created regularly and it is often the case that when one gets a yoga teacher certification (YTT) in a particular yoga studio, they have learned a very specific and particular system that may not even translate outside that studio. This makes finding work teaching yoga very difficult, but that is for another blog.

What I wanted to discuss today is the way systems can help and harm individuals, especially trauma survivors, but including all of us.

Systems are a way of organizing and disseminating information. They help teachers to teach and us to learn and they reflect patterns, categories, and themes which are helpful to understand and be able to identify in teaching. They are never, however, an end all.

Most of us don’t actually fit into one system or way of learning or being.

It’s way more likely that parts of different approaches work best for us or that different yoga styles fit different periods in our life. As a teacher, being able to know many models and adapt for your individual students is a high level and under accessed skill. This is what we teach in trauma sensitive yoga and what we hope more yoga teachers will begin to excel at.

Let’s look at the technique of Tristana, central to Ashtanga Yoga as one example. When tristana, the 3-pointed focus of listening to breath, gazing at one point (drishti), and feeling the body’s position in space is taught in the Ashtanga Yoga model, it is taught as an all-in-one method for experiencing presence, and indeed it is a good technique for that for many people.

Some of us, especially if we are trauma survivors, however, find it challenging to focus on breathing or sometimes to be in our bodies. If it’s forced upon us, it could cause us to feel that we don’t belong or can’t do yoga.

However, with a slight teaching adjustment, Tristana could be the answer for trauma survivors seeking yoga. Instead of instructing that all three focus points must be implemented together, why not use the three-pointedness of the Tristana focus as a way that trauma survivors can move in and out of intensity with subtle shifts? Perhaps putting 90% of the focus on the gaze helps them to stay grounded in the posture. Then maybe they can shift a little more focus to breath on a day they feel more resourced.

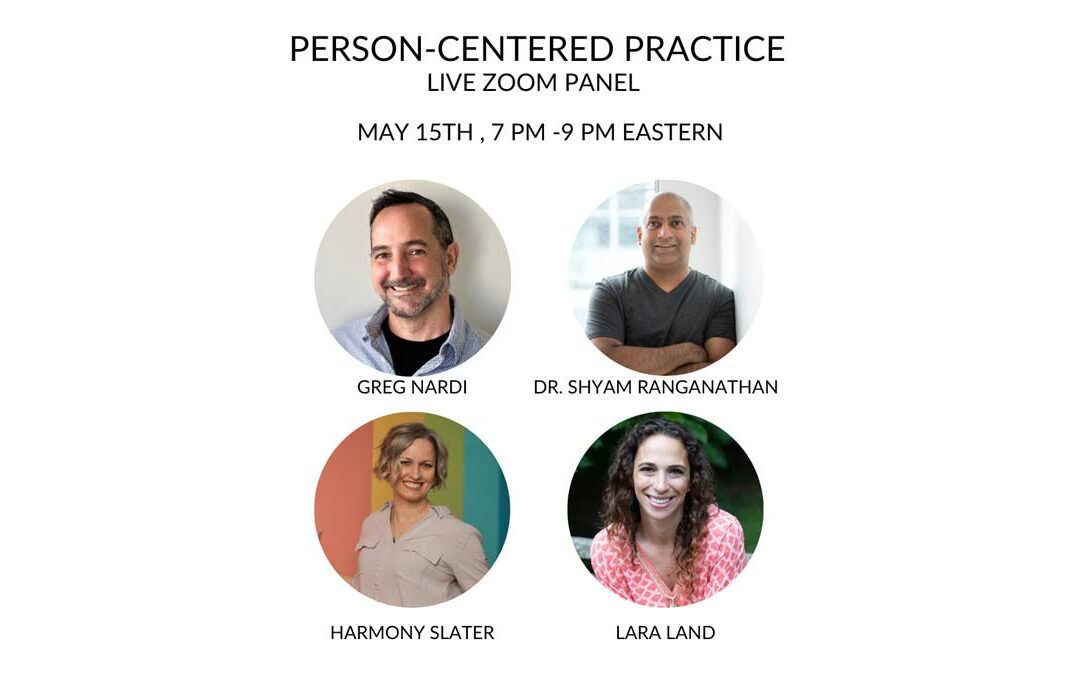

There is so much that can be done here with Tristana and other parts of the Ashtanga and all yoga systems if we just take the time out to think on and get educated on trauma sensitivity, person centered practice and breaking the molds! If this is something that interests you, make sure to take a look at my YouTube talk, book, and sign up for the Person-Centered Practice Panel discussion on Zoom May 15th 7pm – 9pm eastern featuring Harmony Slater, Greg Nardi, Dr. Shyam Ranganathan, and myself.

Recent Comments